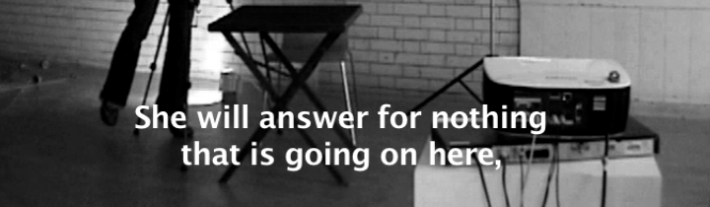

Having been invited to perform at Feint, an exhibition marking the intersection of academic research and artistic practice for postgraduate alumni of Winchester School of Art, I set to work creating a piece that would refract some of my research methodologies through the lens of distraction and misdirection. The result was Postcards from Derrida – S. and p. learn a new trick, a video/performance piece where the audio evidence of two people discussing and rehearsing a card trick was set against written ‘subtitles’ extracted from Derrida’s The Post Card. Against this audio-visual backdrop, I presented the performance by sitting at a card table and playing patience, silently.

All card games, to some extent, hinge on willed disorder. The shuffling that precedes each game acts as a necessary disruptive force that lends the game its momentum through imbalance. The game that proceeds from this point is an attempt, within its own understanding of the term, to seek out ‘order’ – be it through attribution into pairs, sorting into suits, or the establishing of numerical hierarchies – an order that is repeatedly and deliberately thwarted as the rounds proceed. Any resolution found is gathered in, noted and discarded once more, allowing the search for order to continue through a constant wiping of the slate as hands are dealt anew. Whilst resolution is, no doubt, the goal, it is an accumulative resolution that is desired, rather than anything that would put an end to the disorder once and for all. The event that will tie things up is most frequently a token, mutually agreed end-point – the reaching of a certain score, for example. The cards themselves, loose-leafed, are never intended to reach a final ‘perfect’ order in which their optimum position has been determined (for then the answer, surely, would be to bind them into a book), but rather always to accommodate the oscillation between disorder and resolution through which they may continue to operate as playthings rather than enforcers of the law.

The patience player, sitting alone, attempts a different sport. He already holds all the cards – his hand is complete before he starts. He has no one to barter with or second guess – the sole confounding presence is the pack he deals himself and its fall-out of chance upon the table. Time becomes the main opponent. Whilst the patience player no doubt wants to succeed in his final, authorial establishment of order, there is nevertheless a part of him that wants to defer the victory, to return again and again to that point of surrender where he can gather in all he has (which, he knows, is everything he needs) and reformulate it into its old familiar pattern, to subject it again to the usual activities of designation, compartmentalisation and overturning. He knows that, should he triumph, he will have to endure the deflation after victory, the moment spent admiring his coup de grace alone, unrecognised, where the dreaded question comes – what next? Is there any point replaying, when the goal has already been won? Is the success of the player somehow, paradoxically, time’s defeat of him, as he finds his pastime reduced to redundancy in its final formulation?

So here sits the artist-theorist, playing patience alone, fearing that winning the game would somehow thwart her performance, a performance which relies on the deferral of answers, a postcard travelling overseas, awaiting its response. She is Plato addressing Socrates, trusting that the dead cannot answer back, knowing that things, after mortality, cannot help but be open-ended. She listens to rehearsals that never resolve into success, realising the extent of the pack of card’s refusal to reject its natural order. She listens to all the timewasters, the casual conversations, the philosophers talking in what-ifs. She hopes the cards fall badly for her. That way the performance can proceed.

UNTITLED [the preface], 2011. The performance is reshuffled through consideration of rehearsal and the balance of disorder/order that allows things to occur. With thanks to Christopher Piegza and Charlotte Knox-Williams.